Walk With Me

A refugee's journey to freedom

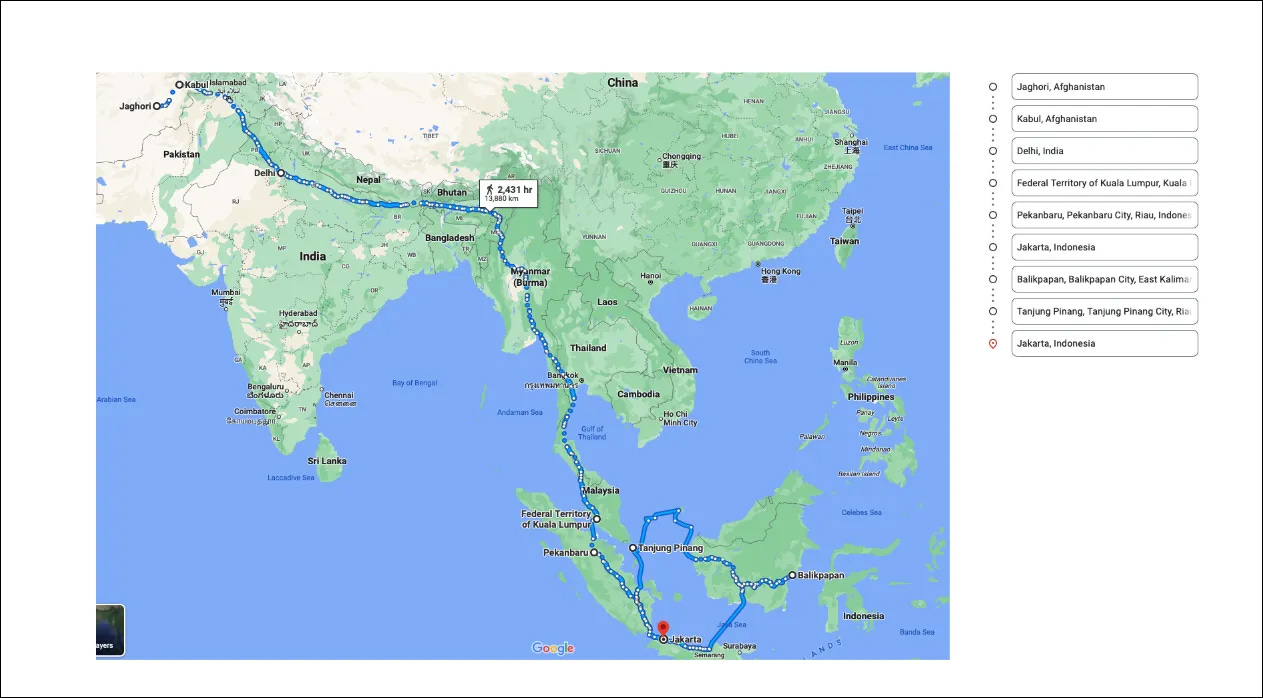

My journey from Jaghori to Indonesia (Google Maps image and WWM logo by Nikie Marston)

I was born in 1998 in a gash of green between arid sharp mountains in Jaghori, Afghanistan. If you look through a satellite image, it all looks like deserted altitudes. Even for a wild reptile this region would be a rigorous place to live. But it’s home to a large number of Hazara—an ethnic minority that has long been persecuted in Afghanistan. Our ancestors were pushed into the mountains as far as the elderly recall from their elderly. Since then, the mountains have protected us.

Of the previous Taliban era that ended when I was still a baby, what I remember is the food scarcity. My mom would feed me her portion of the food – a ladle of rice – and she would go to sleep with an empty stomach. A sudden change washed over the village with the presence of foreign troops in Afghanistan. Our village were freed from the Taliban’s presence. People no longer worried how to feed themselves for the next day. More and more kids started attending school. When I turned seven, with a handmade fabric bag in hand, I went to school – a privilege that my mom and dad did not have, but they encouraged me as much as they did not have the opportunity themselves. My dad, who had the experience of venturing beyond the mountain range, knew the value of education. On the same line of encouragement, I took my sister’s and little brother’s hands on their first days of school. I helped them learn how to read and present themselves in school in ways that I wasn’t guided and struggled through.

In early 2012, a tragic event hit our family when my dad went missing on his way home from bringing shop supplies from Ghazni. The mountains provided security for living, but to survive people relied on outside support. Like many men in the village, my dad sometimes needed to venture outside of Jaghori, facing death threats from the long-bearded men who controlled the border with rifles, just for us to have a piece of bread and for me and my siblings to go to school. My dad’s disappearance saddened the following Nauruz (Persian New Year) for my family. The whole year we waited for him to come. Not even an abandoned corpse was found of him if he was killed like many other men from the village. It left me with a heavy burden to take care of my family, an inheritance that weighed on the shoulder of every eldest son in a family no matter what age he was.

In May 2013, I dropped out of school in grade eight. I reopened our parchon (basic goods) shop that my dad left. It changed the course of our family life. With the help of my dad’s friends, I ran the shop. My mom began having fewer of the urinary tract infections that had worsened after my dad disappeared. My sister and brother continued their education. Smiles reappeared in our home. It filled me with a sense of pride that I was able to look after my family in my father’s absence. I had never been more fulfilled than that.

After over a year of running the shop, I decided to go for the shop supplies myself—something my dad’s friend used to help me with. It was my first experience venturing outside of the mountain borders and through the route that swallowed many people, including my dad. I felt a juxtaposed sense of fright and pride. After our truck had passed through a perilous strip of desert between the mountains and the main highway to Ghazni, the driver and the two other shopkeepers that I traveled with breathed a deep sigh of relief.

In the same strip of desert, two days later on our way back to Jaghori, a few heavily bearded men with spattered uniforms and guns in their hands stopped us. The driver said, “Taliban” in a frightened tone that immediately instilled fear in me. This was the first time I saw Taliban from close up. They savagely went through the truck’s interior, mocking us as they trashed everything with their hands: Hazaragae! Hazaragae! (A mocking word referring to the way we differed in our appearances from them; many Hazara were killed along this route just for their physical differences). Right in the section where my stocks were, they found a box full of alcohol. The truck driver and the shopkeepers pointed at me and said that it was mine - to my bewilderment, as I had no idea how those things got there. It was they who did the loading and I was mere a bystander. I scrambled in a crying voice, screaming that it wasn’t mine; but they did not understand what I was saying. They let the others go in utter humiliation and put me in a rusty white van with my eyes blindfolded.

After some time, I found myself inside an abandoned clayed wall, where four of the black turbaned men threw punches and kicked me. They took my belongings, then carried me to a worn out warehouse. A middle aged Hazara man was there, breathing heavily in the dark, and as I got close I could see through the dim light of the roof window that his clothes were drenched in blood.

The man helped me to escape from the warehouse later that evening. He was unable to walk himself—deeply wounded by the blow he endured from the Taliban. He told me that he was kept there for four days with little food and no medical care. Through the dark, I found my way to the highway – horrifying hours that still send a shiver through my spine. The next day, I hitchhiked on a bus that took me to Kabul.

I couldn’t stay in Kabul, nor was I able to return to Jaghori. Everything seemed out of my ability to grasp. For days, I was in shock. Still sixteen years old, I wasn’t able to fully think for myself, at least not in this circumstance. My mother didn’t want to lose me the way she had lost my father. When she heard that I was in hiding in Kabul, she insisted that I should get out of Afghanistan and sold the family shop to pay my way.

A man from our village who lived and worked in Kabul introduced me to a smuggler. The smuggler said that it would not only save my life; soon I would be able to take my family with me. With that hope in my mind, ten days later, I took a flight to Delhi, India. After a few days, the smuggler took me in another flight to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The smuggler locked me in a private house with twelve other asylum seekers for three days. Then, he took us in two private cars to the Malaysian shore. We walked more than a kilometer in mud and water before reaching a wooden boat, which took us to Pekanbaru, Indonesia.

For the next few days, we stayed with a local family. All seven of us slept in the second floor and the family in the first floor. They shared the food they ate—a plate of white rice with chili sauce and overcooked eggs. I hadn’t eaten a proper meal for days, but I couldn’t eat their meals. Since the day I left Afghanistan, food started changing taste on my tongue. With every bite, I wondered if my family had food as well, if so, did they have the safety of having it? I was the one to provide that food and safety. My mother’s reassurance of working hard with her embroidery work to take care of my siblings kept coming to my mind.

The smuggler took us on another domestic flight to Jakarta, where we registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Soon after, I decided to go to an Immigration Detention Center (IDC). Other people had warned me against the plight of living in a locked confinement, but I had no choice. It was the only way I could go under the support of the International Organization for Migration. And the obscure process of being recognized as a refugee and resettlement to a third country was relatively faster behind the detention wall.

In early October 2014, I surrendered myself along with six other asylum seekers to Balikpapan IDC. But it wasn’t a detention center; it was more like a prison for criminals. We were taken through four highly secured metal-bar doors before reaching the main confinement, which was cut from outside with two layer of walls and razor wire on top. A banner hung from a wire that read, “High Voltage Alert.” CCTV surveilled us from every corner except the cell and bathroom. The security guards saw nothing of who I was and what I had escaped from but treated me as if I had committed the highest treason.

For the next 1,278 days, I lived behind those walls, surviving on a daily bowl of tasteless white rice and a fried fish head. Each of those days often passed like a week – each week like a month – each month like a year. It’s true that time follows a different order behind prison walls. It often sat against the clock, refusing to move on.

More than the detention itself, I was plagued by the deteriorating situation of my family as the Taliban were claiming more and more area in the rural part of Afghanistan. My family was displaced multiple times over the following years. The hardest part has been not being able to do anything to help. It is profoundly emasculating!

Prisons by essence are designed to take away your power. There’s always a push-back from the people inside on giving up their power or not. I found a way to fight back and empower myself by volunteering to cut other refugees’ hair – learning it along the way. Every other day, I trained in Kyokushin (a martial art). At night, I attended English courses taught by a former American troop interpreter.

My hunger for knowledge set me to acquire English within a short span of time, mostly by watching instructional videos on YouTube. Four months before my release from Balikpapan IDC, I started taking photography courses through the online platform Coursera. Despite not having access to proper photography gear, or even to a good cellphone, I strived hard, enrolling in course after course. However, learning photography did not alleviate my helplessness and distress regarding my family’s situation and my own despairing condition. I needed something that could help me determine my own fate and save my day in the absence of family, home, country, culture, society, past, and future.

Finally, in February 2018, I was released to an open shelter in Tanjung Pinang, where I still live today. It was promoted as freedom — living less like a refugee, more like a normal human being. But the reality contradicted that promise when I saw the new, invisible walls that now enclose us: we are banned from venturing beyond Bintan Island, where the shelter is located. Further regulation limits our movement outside of the shelter to daylight hours; a violation of that rule sends refugees back to the detention center for as long as four to five months. Being deprived of the right to formal education, work, marriage, driving, or even buying a SIM card in our own names adds to the debilitating effect of the open shelter.

It is hard to measure the weight of all these restrictions, deprivations, and uncertainty until you see their effects on an individual case. Since 2017, seventeen refugees in Indonesia have taken their own lives either through self-immolation or by putting a rope around their necks – a suicide rate that is significantly higher than among refugees and asylum seekers exiled on Nauru and Manus Islands, with seventeen cases since 2003. Hundreds of others have turned to sedative medicines to numb their pain.

Pursuing self-study has given me the strength to fight back against these odds. Thanks to UNHCR, I have continued to have free access to courses on Coursera. So far I have acquired around fifty certificates from Coursera and EdX. Other invaluable free resources on the internet, including lectures, articles, and e-books, have been a significant part of that self-study. Through my study of psychology, I am now not only able to alleviate my own psychological distress but also to help others around me. I dedicate about twenty hours a week to helping other refugees.

I have also amalgamated my knowledge of psychology with storytelling, in the form of writing. I write short stories, articles, personal essays, and poetry. In 2021, I received a scholarship to WriteSPACE, an online international writing community that has helped me develop and hone my writing skills. The feedback and mentoring that I received from other WriteSPACE members has led to publication of my work in the Cincinnati Review, The Jakarta Post, Project Multatuli, The Other Side of Hope, Southeast Asia Globe, and The Archipelago.

My act of controlling the psychological gear of my distress has been a mere coping mechanism to the underlying issues that have been out of my control. It has been like walking in a lightless night toward a never coming dawn. Sometimes I lose myself to the fear that this long limbo is not coming to an end: nine years and three months have passed since I began my life as a refugee in Indonesia. My helplessness toward the deteriorating situation of my family often darkened my walk. The basic rights I have been denied, the years of incarceration inside prison walls, have been the wild beasts in the walk. During my time in Indonesia, these beasts have claimed the lives of around 60 other refugees.

Fortunately, my decade in limbo is about to come to an end. Through a pilot Community Organization Refugee Sponsorship scheme, I am being given an opportunity to resettle in Aotearoa New Zealand. The dawn of a new life -- an ordinary life -- is on the horizon.

Your support will help me to settle in my new home in New Zealand. With enough paid Substack subscribers (paid subscriptions coming soon), I can spend more time writing and less time working on other jobs. I am also building a scholarship fund to pay for my future university education. You can make a direct donation here. Thank you!